Certification Without Cleansing Leadership Is Institutional Hypocrisy

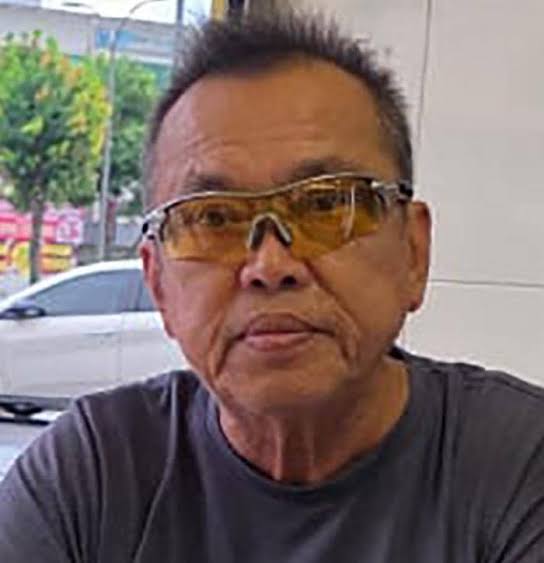

By Daniel John Jambun, President, Change Advocate Movement Sabah (CAMOS)

KOTA KINABALU: Change Advocate Movement Sabah (CAMOS) views the Sabah government’s announcement on pursuing integrated quality and anti-bribery management certification, as articulated by Chief Minister Hajiji Noor, as a misplaced priority that risks institutional hypocrisy rather than reform.

Certifications are not shields against corruption. They are not moral laundering devices. They are administrative tools that only work when the leadership itself is beyond serious ethical reproach. Sabah today faces the opposite reality — a credibility crisis where multiple senior political office-holders and several government-linked company (GLC) chairpersons remain under the shadow of corruption allegations or investigations.

In such an environment, the pursuit of anti-bribery certification appears less like reform and more like reputation management.

The contradiction becomes even starker when placed alongside the recent remarks by Azam Baki, Chief Commissioner of the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC), who described Sabah as one of five Malaysian states considered a “gold mine” for anti-corruption focus due to rapid economic development and elevated corruption risks.

When the nation’s top anti-corruption authority publicly categorises Sabah as a high-risk jurisdiction requiring intensified scrutiny, the Sabah government’s immediate response should be political house-cleaning and transparent accountability, not certification exercises that project compliance while evading responsibility.

The MACC’s own strategic emphasis on enhanced enforcement, holistic prevention, and effective management underscores a critical truth: corruption is not eradicated by paperwork but by visible, impartial enforcement and leadership example. Even MACC has warned against “routine minor arrests” while systemic corruption persists at higher levels. This warning is directly relevant to Sabah’s current governance climate.

CAMOS stresses that anti-bribery systems demand more than internal audits and framed certificates on office walls. They require:

Leaders willing to step aside when under investigation;

Full public disclosure of corruption probes involving state actors;

Independent oversight free from political influence;

Enforcement that reaches boardrooms and cabinets — not merely roadside offenders.

Without these prerequisites, certification becomes a cosmetic compliance ritual, offering international optics while local confidence continues to erode.

Sabah does not suffer from a shortage of governance manuals.

It suffers from a shortage of political courage to enforce integrity at the highest levels.

If Sabah is indeed a “gold mine” for anti-corruption focus, then the first excavation must begin within its own corridors of power, not in the printing of certificates or ceremonial declarations of transparency.

DISCLAIMER: The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Jesselton Times.